CUBA 2025 with The Jazzcat. Let’s GO!!!

LeRoy Downs Sunday afternoon @ 5 pm on KRML.com

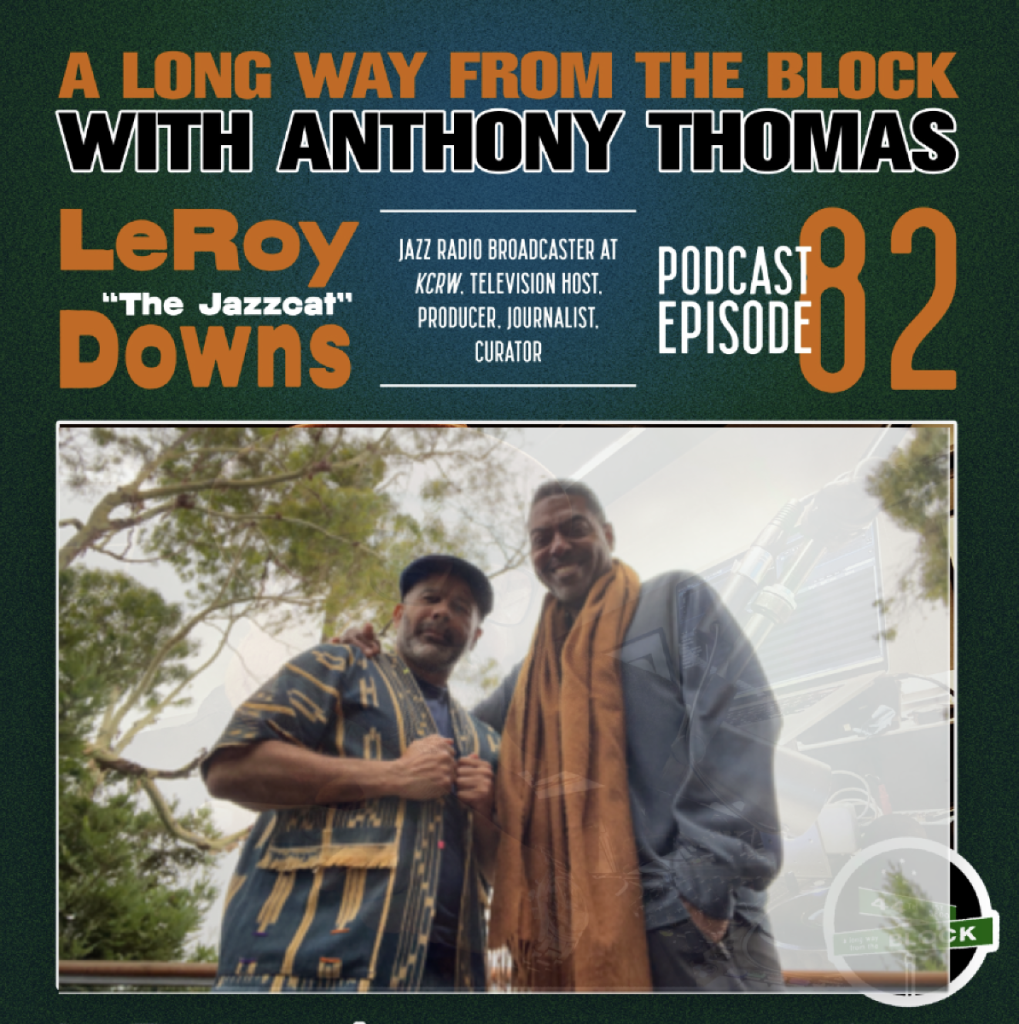

LeRoy Downs interviewed on A Long Way From The Block with Anthony Thomas!!

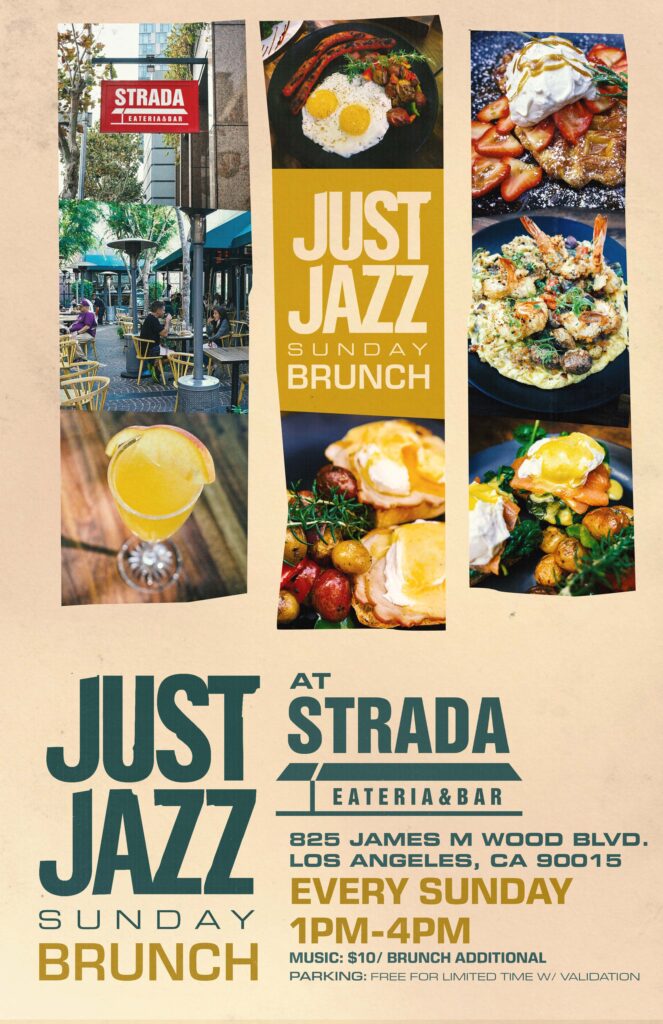

Join Just Jazz For Our Weekly Sunday Brunch @ Strada Eateria Featuring Sounds by Kosta Kutay

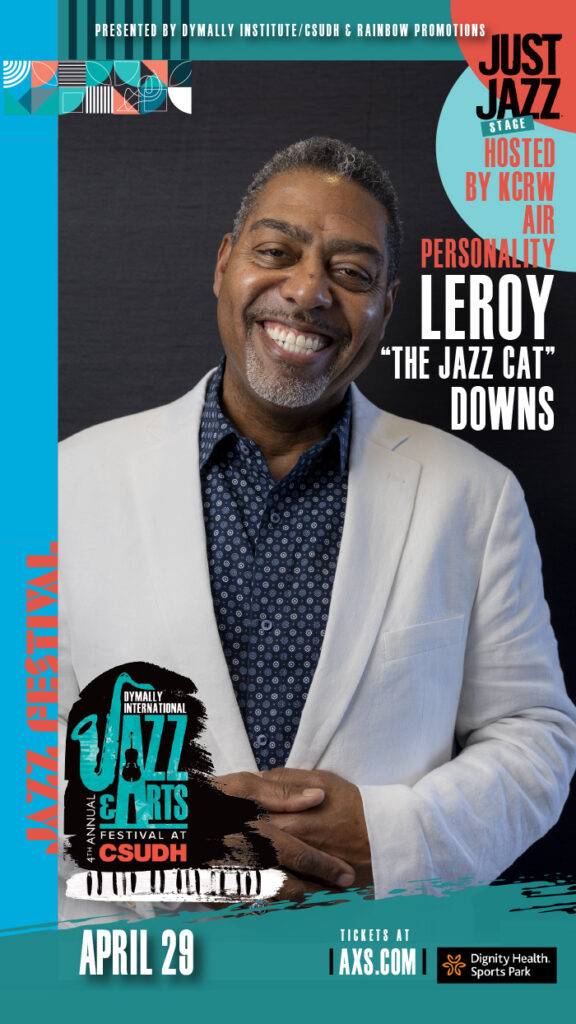

The Dymally Jazz Festival This Saturday With LeRoy Downs and Special Guests on The Just Jazz Stage!

A Very Special Night With Just Jazz & Dan Rosenboom’s ‘Polarity’ Album Release!

April 29th, Join ‘The JazzCat’ LeRoy Downs @ The Dymally Jazz Festival on The Just Jazz Stage!

Join Just Jazz & John Davis For A Night Of Tunes @ The District This Thursday Night!

Howdy. Welcome to The Jazzcat!

Thanks for dropping by! Feel free to join the discussion by leaving comments, and stay updated by subscribing to the RSS feed. See ya around!

Recent Posts

- CUBA 2025 with The Jazzcat. Let’s GO!!!

- LeRoy Downs Sunday afternoon @ 5 pm on KRML.com

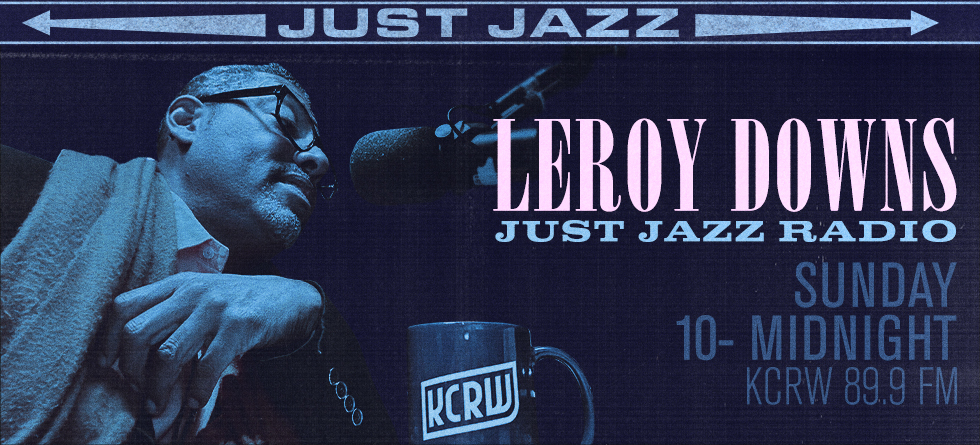

- The Jazzcat Sunday Nights on KCRW

- LeRoy Downs interviewed on A Long Way From The Block with Anthony Thomas!!

- Just Jazz Wednesdays at Seven Nineteen

- Join Just Jazz For Our Weekly Sunday Brunch @ Strada Eateria Featuring Sounds by Kosta Kutay

- The Dymally Jazz Festival This Saturday With LeRoy Downs and Special Guests on The Just Jazz Stage!

- A Very Special Night With Just Jazz & Dan Rosenboom’s ‘Polarity’ Album Release!

- April 29th, Join ‘The JazzCat’ LeRoy Downs @ The Dymally Jazz Festival on The Just Jazz Stage!

- Join Just Jazz & John Davis For A Night Of Tunes @ The District This Thursday Night!

Browse by tags

48th Annual Monterey Jazz Festival 50th Annual Monterey Jazz Festival 2005 IAJE Conference 2007 Chicago Jazz Festival 2008 Chicago Jazz Festival Bennie Maupin Bobby Hutcherson Carmen Lundy Carmen Lundy at the Ford Catalina Bar & Grill Dianne Reeves Dwight Trible Eric Person Gretchen Parlato Hangin’ and havin’ fun with the Jazzcats! John Anson Ford Amphitheatre KPFK 90.7 FM KRML Kurt Elling LeRoy Downs Monterey Jazz Festival New York 2007 New York City Rise San Jose Jazz Festival San Jose Jazz Festival 2007 Temple Bar The Jazz Bakery The Vic Upcoming Performances

Categories

Meta

Log in

Valid XHTML